Few crimes types horrify us more than sexual ones, especially when they involve the abuse of children. Violent stranger attack might make the biggest headlines, but they are dwarfed in scale by sexual abuse carried out by people known to the victim. The viewing of child abuse images via the internet is on an entirely different scale altogether and at epidemic levels.

Quite rightly, in recent years there has also been significant public interest in what has become known as Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG), which includes domestic abuse as well as sexual assaults. This is particularly pertinent in Northern Ireland which now has one of the highest femicide rates in Europe. Domestic violence is hugely under reported and domestic murders are the tip of a huge iceberg of behind closed doors abuse.

One positive however, is that there is strong public support for robust law enforcement in relation to both sexual offending and VAWG. The under reported nature of these crimes and the huge risks offenders pose to the most vulnerable in our society warrants every possible lever to be pulled to police the offenders and protect the vulnerable.

However, in Northern Ireland a multitude of factors are currently resulting in the public (mostly women) being under protected and perpetrators (mostly men) being under policed. This blog focuses on these factors , the impact they are having and what more can done.

Of course there are other components to an effective strategy in tackling sexual violence and broader VAWG. However, the four factors I will now examine require prompt attention; because in combination they embolden and empower predators and disempower already vulnerable victims and potential victims.

1. Sentencing for sexual crimes is getting weaker.

Not every crime is deserved of a prison sentence. Indeed a variety of low level disposal options are helpful in nipping offending in the bud, in a cost effective, compassionate and timely manner.

However, sexual and violent crimes, which are often inflicted on the most vulnerable in our society are different. There are various reasons why tough sentencing is particularly important for such crimes, which I will outline below, but first lets look at the data which proves sentencing for sexual offending is getting softer, whilst offending is increasing.

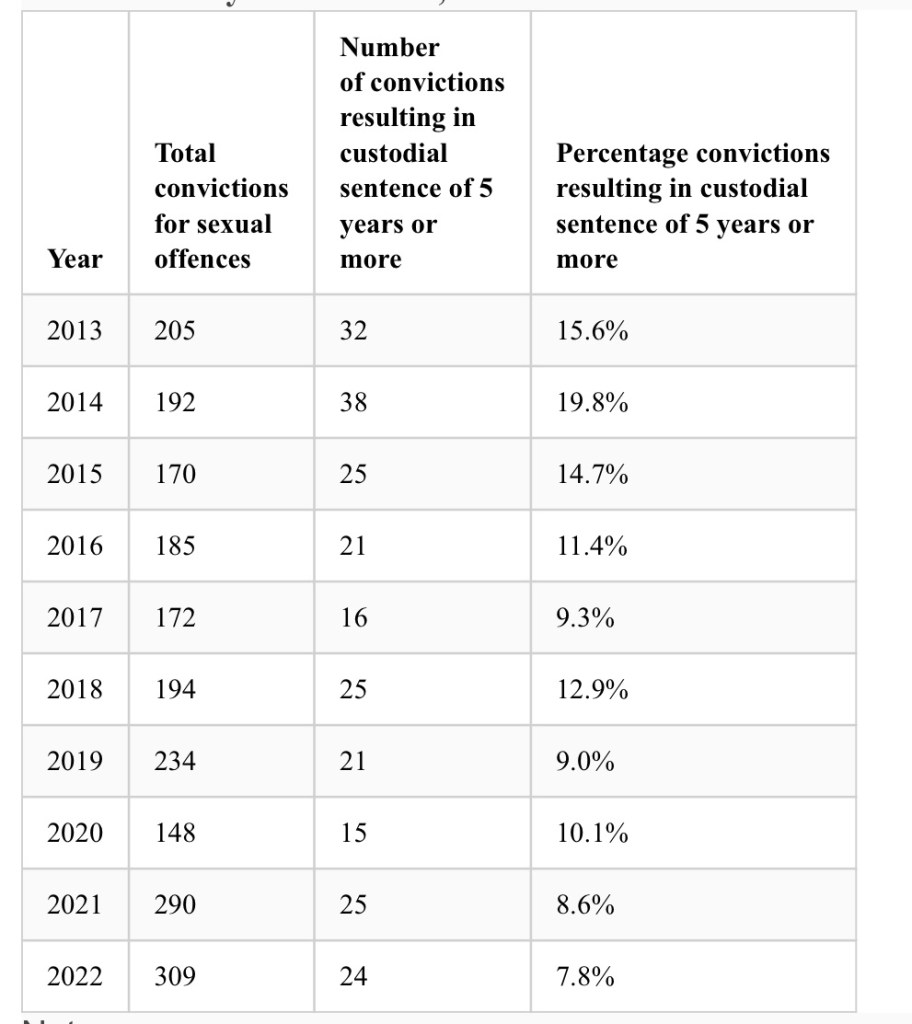

(Information was obtained this year from DoJ after question from Cara Hunter MLA).

The trend is both stark and startling – convictions for sexual offences are up nearly 50 % in 10 years whilst the percentage of those resulting in custodial sentences over 5 years has halved. The perception of weaker sentencing gleaned from scanning media reporting is confirmed by the hard data.

Moreover, scanning news reports in recent years it is particularly noticeable that prison sentencing for possession of child abuse images (especially for first time offenders) is virtually unheard of now. This is very disturbing, as the viewers of these abuse images (that often include babies and infants) are fuelling the demand that sustains the global abuse of children. Huw Edwards soft sentence yesterday is not the exception, it is the rule.

Proper punishments for sexual crimes are essential and prison sentences are particularly important for a host of reasons including :-

1. Sexual offences are hugely under reported, victims need to have confidence that allegations will be treated seriously and result in proper justice.

2. The fundamental purpose of the criminal justice system is public protection, those who pose a risk need imprisoned.

3. Thirdly, the inevitality of a prison sentence for sex offenders and domestic violence (and a much longer one for re-offending) is a vital deterrent. Non custodial sentencing for crimes like viewing child abuse images sends entirely the wrong message to those with perverse interests in children.

What can be done ?

Sentencing in Northern Ireland is the responsibility of Judiciary NI and sentencing is based on precedent and sentencing guidelines. There are weaknesses in both the guidelines and their application by judges.

The impact on the victim is one of the factors a judge weighs up in determining sentencing. However, I am unconvinced that judges fully factor the permanent trauma to victims from domestic and sexual abuse. The murder of Katie Simpson by Jonathan Creswell is a prime example.

Creswell has previously received a pathetic six month sentence for the strangulation and prolonged abuse of Abi Lyle; yet it was clear in the recent media interviews the profound long term impact this ordeal had on her 15 years after the incident.

Inexplicably, Creswell was on bail even during his murder trial, despite the seriousness of the charges, his previous conviction and his protracted efforts to conceal his crime and influence witnesses.

Everyone in the criminal justice system needs to ensure the impact of sexual offending is understood and carried through to bail/remand applications and crucially sentencing. This requires more than the use of victim impact statements being read in court.

Everyone involved in the criminal justice system needs more awareness training on the life long impact of sexual offences in particular and of the recidivist and often escalating nature of domestic violence.

Judges who seem reluctant to jail those who view and distribute even the most extreme categories of child abuse images, need proper awareness training of the causal connection between the case in front of them and the actual victim in another part of the word. Viewing an indecent image of a child in Moira fuels the sexual abuse of children in Manilla.

The credit that defendants get for guilty pleas is another area that needs tightened. Often a defendant denies responsibility right up until the trial date and when faced with overwhelming evidence and knowing that their victim hasn’t ‘pulled out’ of the case he enters a plea. I have read reports of the defendants getting significant sentence mitigation in such circumstances, this is utterly perverse.

In such cases, a late plea does not display genuine remorse, nor does it save significant legal costs (a factor in rewarding pleas). Crucially, it does not spare the victim the ordeal of going through a protracted criminal justice process and the painful disclosure exercises. It merely avoids the few days or weeks of the actual trial and as such no credit should be awarded whatsoever. Giving credit to late pleas is a disincentive to early pleas.

The Justice Minister has consistently stated that sentencing here is nothing to with her and is solely the responsibility of Judiciary NI. That is not how liberal democracies work. Whilst individual sentencing is always a matter for judges alone (with the caveat that unduly lenient sentences can be appealed via a prescribed process) the overarching responsibility for the effective delivery of justice in Northern Ireland lies with elected politicians.

The Justice Minister is absolutely entitled to commission a review of how we deal with sentencing in Northern Ireland and to examine with all the justice agencies how a victims voice and trauma is better heard and understood throughout the criminal justice process.

Fresh sentencing guidelines can be drafted and developed that reset the balance of factors that Judges weigh up, so they are more supportive of victims and better protect the public. Once finalised, it is for judges using their operational independence to implement them, hopefully in a more trauma informed way.

2. The criminal justice system in Northern Ireland moves at glacial pace.

I shall make this sub-section brief, because it is universally agreed that our justice system here is too slow.

Justice delayed really is justice denied when it comes to VAWG and sexual offending cases, because the longer a case takes the higher the drop out rate of victims is. The mental anguish of complainants is great and their resilience finite and sadly defendants know this. Delay is a defence tactic as much as a systemic flaw.

There are some immediate steps that could be taken and we await to see what the draft PfG will herald (it did include a priority to tackle this issue).

So what can be done ?

The sentencing guidelines could be amended (in text and application) to properly disincentive late pleas. Defendants who are guilty need to know, that denials and delayed pleas will result in exemplary sentences. Credit should be reserved for very early pleas and remorse.

Proper case management is another thing that is not done properly here. Contested issues and contested evidence are not whittled down as expeditiously as they should by the PPS and defence long before trials.

By way of illustration, this is why police officers will spend days on standby at court, but rarely be called to give evidence.

The PPS frequently request that every witness in a case attends court, instead of agreeing with the defence non contentious one (like the officer who has transported an exhibit). Proper case management triages the issues at the crux of cases and done well would streamline our entire justice system.

These are just two options of many, but action is needed. Recently a case was resulted that involved a sexual assault, it took over 7 years for it to work through our justice system. This is beyond ridiculous.

Perversely, the delay in a case is often used to justify a lenient sentence, indeed this is a mitigating factor in the sentencing guidelines. An elongated criminal justice process punishes the victim and rewards the defendant.

3. PSNI policy on releasing mugshots reduces public awareness and confidence.

Lord Hewart’s famous dictum, that “justice must not only be done, but must also be seen to be done” is as true as ever. In Northern Ireland, not only are victims of serious crimes being let down by weak sentencing, but also by a lack of visible justice.

Throughout the UK, police services routinely release post conviction mugshots of defendants to the media on request. The national guidance supports this and strongly so if the defendant received a custodial sentence of 12 months or more.

The PSNI do not follow this guidance and as a matter of routine, it declines all media requests for mugshots. This is pure risk aversion, unfortunately a culture of which was created by the extreme levels of accountability and criticism that policing here endures.

By not releasing mug shots (which are high quality recent photographs) the defendants in cases such as rape, domestic abuse and other high impact crimes are protected from appropiate exposure. Victims are robbed of the sense that their perpetrator has been unmasked (especially important in behind closed doors crimes).

When the public see the face of the convicted defendant someone may recognise the person who has committed crimes against thems and so be able to report it. And vitally, there is an up to date photograph of the defendant in the public domain, so women in particular can in future check who it is they are coming into contact with (even more importantly because criminals change their names, see below).

Currently, we rely on the media getting hold of an old picture of the defendant or a snatched photo of him or her entering or leaving court. Criminals know this and walk to court with often ridiculous looking face coverings on. This is absurd and an affront to open justice.

One issue that has concerned the PSNI about releasing images is one that I previously exhaustively considered when releasing images of suspected rioters (hundred of them between 2009-2018). The PSNI has been spooked by the spectre of paramilitarism and the fear that the released photographs might be used to target people for ‘punishment style shootings’.

In fact there is no evidence base for this fear and previously when images have been released no such harm has resulted. Ultimately, so called paramilitaries actually exploit the sense that there is a justice void in Northern Ireland and the best way to undermine them is to show that the criminal justice system works effectively and to maximise the publics trust in it.

So what can be done?

The Chief Constable should change the PSNI policy and practice in respect of this issue and adopt the national practice, which is straightforward and has stood the test of time.

Doing so, would be an easy win for the (relatively) new Chief Constable in repairing what has gone wrong in policing here and is an opportunity to stand stoutly on the side of victims of crime.

The general public and victims would see the faces of those convicted of sexual crimes and VAWG as well as other serious crimes like burglary. Victims who have not reported crimes are more likely to come forward and some will even recognise their perpetrator’s and file a report. Women and girls in particular will be better empowered to protect themselves against repeat abusers going forward.

I’ve said before the PSNI should be on the front foot, not the back foot in the media and this is an opportunity to reset.

4. Sex offenders and domestic abusers can change their name in Northern Ireland

Unlike in England and Wales, here in NI sex offenders can legally change their names to protect their identity. Of course they have to advise the police if they are being monitored and on the Sex Offenders Register, but that only offers limited reassurance to the public. In any case, domestic abusers are free to change their name too.

Changing one’s name is fairly easy and in an era of social media and internet dating, men who have convictions for domestic assaults have an incentive to change their name to conceal previous offending (men and women who have convictions for stalking do as well).

Sexual predators and domestic abusers often carry on offending and they target vulnerable people. Imagine you have a vulnerable friend or relative who is associating with someone you have concerns about, perhaps having seen red flag behaviour.

Internet checks will not expose that persons history if they have changed their name and if their mugshot was never released recognising them is out too. The combination of post conviction mug shot for abusers not being released and the ease of changing your name provides de facto anonymity to predators.

What can be done?

There is legislation that can be imported from England and Wales swiftly and easily to make it illegal for sex offenders here to change their names.

However, we can go even further and given the problems we have with domestic abuse and femicide, extend the prohibition to include those convicted of domestic violence and other crimes like stalking (watch Baby Reindeer on Netflix and you will see why this is important).

Conclusion.

In Northern Ireland too often, the balance of human rights considerations are weighed improperly in favour of the defendant over the victim. This is true of the entire justice system. Also, too often the PSNI have been browbeat into being defensive and risk averse instead of proactive and protective.

It is now time for sentencing for sexual crimes, VAWG and other serious crimes to be stiffened, for the PSNI to adopt national practice and release mugshots and for those convicted of serious crimes to be stripped of the ability to change their names and conceal their identity. This all needs to happen within a criminal justice system that is faster and more victim focused and trauma aware.

The most vulnerable in our society are being under protected by our criminal justice system in Northern Ireland. If we put victims first, we will likely have less victimhood in the future.

The NI Executive has just published a new VAWG strategy, let’s hope there is action and not just words.