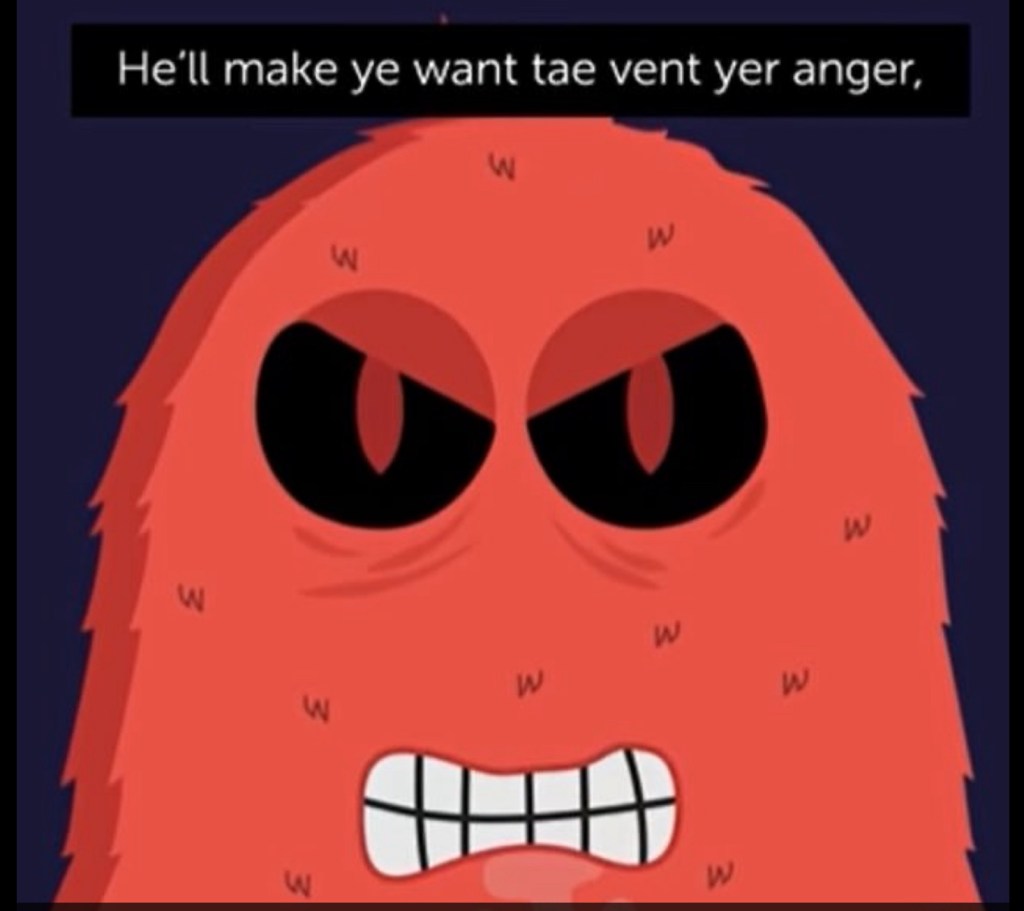

Police Scotland have had a decidedly unfavourable response to their deployment of Hate Monster.

The reaction has ranged from derision to ridicule; so much so that the negative feedback may prove fatal to Hate Monsters’ fledgling career.

It is somewhat surprising that a campaign designed to highlight prejudice, actually singled out 18-30 year old white males from socially and economically deprived backgrounds for negative stereotyping.

The use of a cartoon character by a police service on social media, took me back to 2016 in the PSNI. That was the month that the PSNI Craigavon social media team deployed dissident Dan, the terrorist stickman.

Dissident Dan began his active service as our PR agent in January, delivering a withering and satirical counter offensive against the Lurgan dissident republican terrorists who liked nothing better than to leave suspected explosive devices on the railway line.

Not content with just disrupting railway passengers; the dissidents would then orchestrate riots against the police when they closed the railway line and set up sterile zones for the army to examine the devices.

The day before Dan made his debut; over 100 petrol bombs were thrown at the police in Lurgan and a gunman used the cover of children rioting to attempt to murder officers.

The railway line ran right beside the Kilwilkie estate; an area of high social deprivation in which the Continuity IRA still held sway. It was easy for them to leave devices and whip up trouble.

Security operations to clear suspect devices were very slow, as there was always a risk of a deadly secondary device being left for the police. The disruption to the community and railway users was always immense and the cost to Translink who operate the rail service was substantial.

Something novel was needed to connect with the young minds that were being led astray by warped terrorists. Something different was required to shame the terrorists into stopping the attacks on their own community.

And in truth, something new and different was needed to penetrate the culture of complacency in a society that just shrugged their shoulder when this sort of low grade, high impact terrorist disruption was taking place. Cue dissident DAN.

Dan the stickmans words cut the dissident republican narrative of resisting British imperialism by attacking a train line to ribbons. It shifted the narrative from terrorists attacking infrastructure, to an attack on the people who used the train and lived beside the railway track.

And frankly, Dan also humiliated the local “hard men”. One community activist told me that “Dan drained their authority in a single post, their swagger was gone , it was pure genius”.

Because, in addition to laying bare the attacks for what they were (cheap shots in a failed campaign, at the expense of ordinary people); Dan brilliantly undermined the prestige of terrorism and the image of the terrorist that extremist organisations rely on for recruitment and radicalisation.

This is vital in preventing young men from socially and economically being drawn to being groomed by such groups. Dan was a naked stick man, stripped of the trappings of status, wearing nothing but a balaclava. He was a figure of derision.

Dissident Dan was loved by all and he went absolutely viral, reported in national newspapers and further afield. Well nearly loved by all, because of course the dissidents loathed Dan. He was the talk of the young people, because he was on the social media platforms they got their news from and he made them laugh. Laugh and stop to think.

Before long teenagers, many from schools that dissident republicans actually recruited from, were asking to do their work experience in Lurgan police station. They wanted to meet Dan and his legendary creator M, whose mysterious moniker had signed off on a series of engaging and entertaining social media posts.

And dissident Dan really was a golden goose and that is no fairy tale.

The engagement between young people in the local community, which had high levels of social and economic deprivation increased exponentially. Dan boosted the good work local neighbourhood police in the district had been doing for years.

This was combined with other work, like rigorously investigating those who were involved in the riots and relentlessly using social media to demonstrate effective policing. Everyone from the Commander, Superintendent David Moore to every new Constable was invested in our strategy.

Believe it or not within months we witnessed the end of the railway line closures as terrorists dared not risk online ridicule and a backlash by dissident Dan and his posse of followers. Serious public disorder in the area ended. 100,000 people were following the local police Facebook page.

The tide had turned.

Winning hearts and minds is good counter terrorist policing as well as good community policing; and being novel about it is both smart and necessary.

Whether it be domestic terrorism or extremist ideology, there is always the ‘myth of the cause’. The distortions, exaggerated grievances and warped messaging that makes irrational and immoral acts seem logical and noble.

Because ‘insurgent leadership is often competent and adaptive’, so must be an effective counter-insurgency strategy (quote is from “Counter -insurgency and the Myth of The Cause”, Journal of Strategic Security 2015).

Whilst ‘counter insurgency’ is language more akin to the military than civic policing, the point is the same. The dissidents were exploiting social media to advance their narrative, they had multiple channels. so that’s where local media engagement needed to be.

But it has to be snappy, engaging, accurate and vitally be able to connect with the target audience without offending the wider one. Dissident Dan, the balaclava sporting stick man, hit the note perfectly.

Dan was a key part of a wider plan, that undoubtedly degraded the capability of local terrorists and built relations between the police and young people most at risk of exploitation.

Like many of the best turned agents, Dan has a short career. By July the job was done and he was retired from active service; not without chalking up more successes. Of course, you can’t make omelettes without breaking eggs, and Dan broke one or two.

The Hate Monster got a bad press; but not because such tactics cannot work in policing. It was the design and execution that was poor, not the concept. The messaging was wrong, the humour didn’t work and it felt like an exercise in virtue signalling.

Dan connected with the young people who were vulnerable to manipulation, instead of alienating them. That was Dan’s strength, but Hate Monster’s failing.

I hope police leaders don’t write off innovation and humour on social media as a legitimate tools in their armoury. That would be a strategic error. Innovation is not without risk, but the rewards can be considerable and often without incurring much cost.

Dissident Dan was the man. Be like Dan.